World Exclusive! Kramer GP2 Prototype – First Ride

This is what dreams are made of

Markus Kramer said it so nonchalantly when I asked him. “Three months ago,” he said. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, so I asked in a different way. “You mean to tell me this motorcycle didn’t exist four months ago?” Again, the response was simple. “Yep.” Markus isn’t a man of many words, but that’s when I knew this ride aboard the GP2 Prototype from Kramer Motorcycles was going to be different. I shouldn’t have been surprised. Back when KTM’s 790 Duke was first announced, I knocked on Joe Karvonen’s social media door, asking the sole importer for Kramer Motorcycles USA whether the 790 Twin engine would make its way into a Kramer.

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

Since you’ve probably never heard of Kramer Motorcycles, the four-year-old German company is headed by Markus Kramer, a former KTM employee who decided to go rogue and build his own motorcycles ( more on him in a separate story). Specifically, he builds race-ready, track-only (as in not road legal) sportbikes powered by KTM engines, wrapped in bespoke frames of his design, with WP suspension components suited to each specific customer. Building a track-only sportbike is a niche within a niche, and one partially filling the gap KTM itself no longer chooses to participate in (that’s sportbikes, in case you couldn’t guess, the RC390 notwithstanding).

Trizzle’s Take: Markus Kramer, the Man Behind Kramer Motorcycles

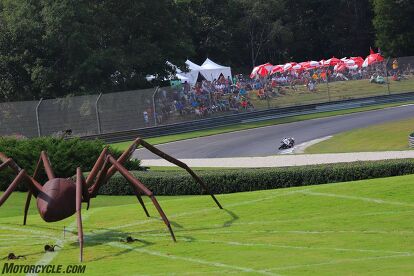

After enough pestering from me, Karvonen finally admitted there was something in the works but swore me to secrecy. As it turned out, the grand plan was all centered around the Barber Vintage Festival. Kramer would unveil a new motorcycle – the GP2, powered by the 790 Twin – and thanks to my constant pestering, Kramer and Karvonen gave me the green light to ride it. See? The squeaky wheel gets the grease after all. The catch? The GP2 would be a prototype, meaning there would be some bugs to work out. I just hoped the bolts were all tight…

The fact this plan was even happening at all is what I love about small companies, and they don’t get any smaller than Kramer Motorcycles. With only three full-time employees – Markus Kramer, his wife, and assistant Matthias Bock – Kramer Motorcycles doesn’t have the luxury of huge test teams like the big boys do. This is only a little bit alarming considering Kramer builds race-only motorcycles (don’t worry, he does have one test rider, former KTM European Junior Cup competitor Lukas Wimmer), but having ridden the company’s first offering, the excellent HKS EVO2, powered by KTM’s 690 Duke Single, I knew I was in good hands.

You see, in this job, us journo types don’t generally see motorcycles that are still in their infancy. When a big manufacturer like Honda hands us the keys to their motorcycles, a team of test riders and engineers have developed a few iterations of the machine in private, far away from the public’s eye. By the time the media or the general public throw a leg over a motorcycle, it’s the finished product. All the T’s have been crossed, the i’s are dotted, and (hopefully) the bolts are tight.

Full Factory? Not Really

On Wednesday, when I landed in Alabama for the Barber Vintage Festival, the motorcycle had only arrived two days prior – in pieces. Karvonen scrambled tirelessly the day before putting the whole thing together, going so far as to rent shop space at a local dealership to get the job done. A MotoGP-like factory race effort this definitely was not…

Not that a big-buck effort was what we wanted anyway. Here we were, a small group comprised around a journalist hack, on the ground level of a new motorcycle’s development. My input would actually have some sort of meaning (or at least I hoped it would). Unlike the usual rides I get invited on, this motorcycle was far from finished. In fact, it was just beginning. This was going to be fun.

Because the GP2 was so new and Markus Kramer only had three months to put a bike together before Barber, there were many unknowns. Firstly, instead of designing an all-new frame for the bike, the 790 Twin sat inside a modified frame of Kramer’s first model, the EVO2, which was originally designed for KTM’s 690 Single. Frame spars were “massaged” (ok, they were cut and welded) to fit the extra cylinder. A wider swingarm was also fitted to accept a 180-series rear tire compared to the 160-series rubber more commonly used on the EVO2.

Due to a lack of development time, the stock KTM electronics, ECU, and software were kept on the GP2 in order to get it out the German door and shipped to Alabama in time. Various sensors to optimize the 790 Duke’s rider aids – like wheel speed sensors and such – didn’t make the cut because of the time crunch, so only necessary electronics to make the engine run were kept. This meant the OEM quickshifter and traction control weren’t functional. The only performance add-on was an exhaust system. It made the GP2 one of the best sounding bikes in the whole paddock, but the fuel mapping wasn’t altered one bit for the exhaust – for all we knew we might have actually hurt our performance! Our best guess was about 100 hp to the wheel, similar to what the 790 Duke puts down.

Otherwise, from a component standpoint, the GP2 Prototype is hard to distinguish from its EVO2 cousin. It still uses WP suspension, forged wheels from Dymag, and dual 290mm discs with Brembo M50 calipers. Even the bodywork was the same (which won’t be the case on the final production model). To me, the coolest single feature of Kramer Motorcycles is the composite fuel tank manufactured by Slovenian company Roto, that also serves as the tail section, subframe, and rider seat. It’s a simple yet elegant, efficient, and effective design.

The Game Plan

Being uncharted territory, the GP2 was all new to everyone. Sorting it meant riding it as much as possible. Even Markus Kramer himself made the trek from Germany to Alabama, along with right-hand-man Matthias Bock, to see his newest baby take its maiden voyage. If he had done his math right, there wouldn’t be much for him to do. Luckily, Markus also knows his way around a toolbox in case the math was wrong.

For the Barber Vintage Fest, AHRMA (the American Historic Racing Motorcycle Association) earmarks Thursday and Friday entirely to practice, with Saturday and Sunday being race days. Needless to say, we’d need to take advantage of both practice days, with the high probability of using the races as additional testing time, too. To that end we entered the GP2 in five races, one of which was the Pro Challenge, with the winner taking home $8,000 of a total $18,000 purse.

With actual money on the line, the fastest riders on the fastest bikes would be battling it out for glory. Names on the entry list included MotoAmerica and World Superbike competitor Geoff May aboard his EBR superbike, former MotoAmerica Superbike rider – turned Dunlop test rider – Taylor Knapp aboard a Ducati 1199 Panigale, and British Superbike star Tommy Bridewell aboard a custom Pierobon chassis powered by a Ducati 1299 engine. At the tail end of the list was my name, on a motorcycle with half the power as the top guys – and even less talent to boot. No pressure, but there was definitely no backing out now.

Things got off to a bad start as I didn’t even complete my first lap before I had to bring it back. The suspension settings were entirely too stiff for my liking, and by the time Karvonen and crew adjusted the clickers and changed the preload, there were only a few minutes left in the session. Nonetheless, bringing the GP2 across the line for the first lap in practice brought cheers of joy from the team. From there we were constantly chasing suspension issues, as no matter what we did the bike always felt too stiff – I was bouncing over bumps instead of having them get absorbed by the suspension.

Being slightly heavier than the single-cylinder EVO2, Markus figured heavier springs were needed on both ends. It took less than a lap to figure out this wasn’t the case. Unfortunately, it took much longer to find the lighter springs we needed. It was a minor miracle we were able to find lighter weight springs for both the fork and shock from our own parts bin and the parts bin of other riders in the paddock, and doing so changed the attitude of the bike completely, providing more confidence to carry more corner speed and allowing me to feel more comfortable getting on the gas earlier.

Miraculously, there wasn’t much else to complain about with the bike. It scrubs speed like nobody’s business, changes direction with ease, and is still plenty quick while still on its side – something I would soon learn to take advantage of, as the GP2’s downfall was its lack of straight-line speed compared to the other machines it was up against. Opening the gas early and often is mandatory on the GP2, and I was happy to oblige to hear the 790 Twin roar.

It’s Go Time

Come the big Pro Race on Saturday we were still sorting out little issues, trying to fine-tune setups with the limited time we had. Nonetheless, it was time to head to grid for all the marbles. Sitting on the grid, it was clear our little GP2 was down on power compared to the Ducatis, EBRs, BMWs, and even a Triumph 675 Daytona. Starting from seventh on the grid out of 11, a decent start meant I wouldn’t be last by the end of the first lap. Surprisingly, thanks to the Kramer’s agility, I held on to my seventh place position for most of the race. However, once the trio of May, Knapp, and Bridewell flashed by me and put me a lap down my concentration lapsed, allowing Tom Wilbert on another Ducati-powered Pierobon to put me down a position.

While the result wasn’t amazing, I was inspired by the fact the GP2 could hang with the big boys, but there was still more time to be found, as I saw other machines getting better drive on corner exits than I could. Enter Oscar Solis of Pirelli, who suggested I try the SC0 compound – the softest available – of the Diablo Slick in a 180/60-17 instead of the 180/55-17 SC2 I had been using. His reasoning was two-fold: First, Solis explained Pirelli’s latest developments have been put into the SC0, whereas the SC2 haven’t seen much change. Second, the taller profile would put a bigger footprint on the tarmac at full lean. Combine that with the added grip and I should get better drive. It made sense to me, so we slapped the tire on.

With no practice time on Sunday, the first I’d get to try the new tire would be in my first race of the day, Sound of Thunder 2, with various machines like Triumph Daytona 675s, BMW Rnine Ts, and EBR 1190 RXs, among others. Wouldn’t you know it, Oscar was right! Within the first three laps of trying the new tire, it was a clear step better. Not only did it feel like I could lean the GP2 over further, but also I could carry more speed leaned over, and sure enough, I felt more comfortable opening the gas earlier on exits. An unintended benefit was the slight change in gearing, which proved really helpful through the sweeping corners of the track, as I could hold a gear a little longer before hitting the limiter. The timesheets also didn’t lie – we dropped nearly a second off the times, ultimately finishing fifth in a field of 38.

By our last race of the day, Formula Thunder (again, a class where the big boys on the big bikes come to shine), we had tweaked the bike as far as we could with the equipment we had, and though the tire change made a big difference, some more time to play with geometry and suspension could have brought us even further. Still, with nearly 30 motorcycles to contend with, I was starting to feel confident of our chances to do well.

At the start, Tommy Bridewell – BSB frontrunner, don’t forget – took off and wasn’t seen again. This left Pierobon-mounted Tom Wilbert and I battling it out for the remaining spots on the podium. The entire time it was a seesaw affair; Wilbert easily distanced me with horsepower, and I would catch it all back in the corners, the GP2’s amazing agility – and its power deficit – was on full display. On the last lap, the only hope I had was a Hail Mary dive on the inside on the last corner, hoping the pass would distract Wilbert just enough for the Kramer to squeak to the line. Having lined him up for the entire lap, when the last series of corners came, the opening was there for the taking. After the dive, the only thing left was to stretch the imaginary throttle cables, but it was no use; Wilbert easily powered by me at the line. Third was the best I could hope for.

Or was it? Little did we know, but Bridewell decided to enter the pits to make changes to his bike, putting him several laps down and meaning Wilbert and I were fighting for the win! Ultimately it wasn’t meant to be, but the real key ingredient missing from the GP2 is power. Considering the 790 engine was as stock as they come – and the fact the motorcycle didn’t even exist four months prior – the whole team was nothing but happy with the GP2’s debut race weekend. It turned heads and came 0.160-second away from bringing home a first place trophy.

What does the future hold?

Where do things go from here? Well, clearly this prototype proved itself, but it also highlighted areas to improve. Power being the single biggest thing, but there’s more possible with the suspension and chassis geometry. Markus Kramer promises the production version will be even better and will deliver the power needed to compete with some of the bigger bikes we were up against. Being a man of few words, when I asked if bumping engine displacement was the answer, he just looked at me and smirked. Cheeky…

Being a prototype, it might be a little early to say what’s to come of the GP2. Looking at Kramer’s current model, the EVO2, it’s available in two variants: the “lower” spec S and the “no-expense-spared” R, so expect the GP2 to follow suit. Again, it’s too early to know pricing, but the beauty of Kramer Motorcycles is their relative affordability. At $16,990 for the EVO2 S, you get a true “Ready To Race – and win” motorcycle. Try doing that with an R6. Rest assured, the GP2 is going to be a weapon. And if you don’t end up liking it, feel free to blame me.

Troy's been riding motorcycles and writing about them since 2006, getting his start at Rider Magazine. From there, he moved to Sport Rider Magazine before finally landing at Motorcycle.com in 2011. A lifelong gearhead who didn't fully immerse himself in motorcycles until his teenage years, Troy's interests have always been in technology, performance, and going fast. Naturally, racing was the perfect avenue to combine all three. Troy has been racing nearly as long as he's been riding and has competed at the AMA national level. He's also won multiple club races throughout the country, culminating in a Utah Sport Bike Association championship in 2011. He has been invited as a guest instructor for the Yamaha Champions Riding School, and when he's not out riding, he's either wrenching on bikes or watching MotoGP.

More by Troy Siahaan

Comments

Join the conversation

Wicked, that is one of the best stories, and certainly the best Bike video I have seen. Wow I would love to own and ride one of those bikes, the amount you were able to make up under braking and cornering is amazing. Light makes right. Well done Kramer, I hope one day to have enough dosh to own one of your bikes. Cam

More will be expected for this bike as the team behind it is very much exposed to the racing world.